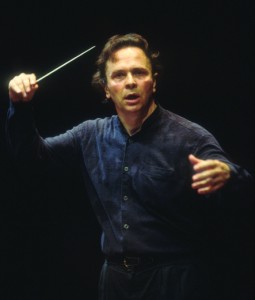

MARK ELDER talks to AMANDA HOLDEN about BERLIOZ

In mounting a new production of Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, ENO is returning to one of the works that shaped the company’s profile soon after its move to the Coliseum from Sadler’s Wells nearly thirty years ago. And returning to conduct it is Mark Elder, ENO’s music director throughout the 1980s. This will be Elder’s third new production at the Coli since he left in 1993. His first guest appearance was for Lohengrin, the second was Tristan and Isolde, with David Alden, who will now direct The Damnation of Faust.

In mounting a new production of Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, ENO is returning to one of the works that shaped the company’s profile soon after its move to the Coliseum from Sadler’s Wells nearly thirty years ago. And returning to conduct it is Mark Elder, ENO’s music director throughout the 1980s. This will be Elder’s third new production at the Coli since he left in 1993. His first guest appearance was for Lohengrin, the second was Tristan and Isolde, with David Alden, who will now direct The Damnation of Faust.

Elder has a very special affection for Berlioz’s music and hardly a year has passed when he hasn’t included Berlioz in his international concert repertoire. `He, Berlioz, has always been there for me. Beatrice and Benedict [which Elder conducted at ENO in 1990] was one of the operas we put on when I was an undergraduate at Cambridge in the late 60s. I was the repetiteur and the conductor’s assistant. I also played the bassoon in the orchestra, so I was in on the whole genesis of that production. My enjoyment of and involvement in opera started then, with that sense of being a part of the process. I shall never forget how thrilling it was to play in the middle of Berlioz’s particular sound world. Very soon after that I decided that Romeo and Juliet and The Damnation of Faust were two of the most important 19th century personal achievements. If I now had to pick fifteen outstanding works from that century, those two would be there.

From the moment Berlioz first encountered part I of Goethe’s great play, in Gérard de Nerval’s translation, he was hooked. In 1828-9 (at the age of 25) he set eight scenes from Faust. Though he published this piece, for soloists, chorus and orchestra, at his own expense as opus 1, he soon withdrew it thinking (as he says in his memoirs) the work was crudely and badly written – he rounded up all the copies he could find and destroyed them. Nearly twenty years later – still obsessed with the Goethe – he decided to attempt another Faust composition and, perhaps with hindsight, incorporated some of his earlier material into a new work. This four-part piece is not a `conventional’ opera in any sense, but rather a series of lyrical scenes, based loosely around the Faust story, and as such – it was successively called grand opera, concert opera, opera legend and finally dramatic legend – it is unique in the operatic canon.

The quixotic and mercurial nature of the work perhaps reflects the spirit in which it was composed – part of it, literally on the hoof. As he bowled along in his post chaise on a tour of Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and Silesia, Berlioz wrote the score with an ease he rarely experienced at any other time. The music flowed out of him as the ideas occured, regardless of where he happened to find himself; the choral refrain of the Peasant’s Dance was written by the light of gas-jet in a shop in Pesth, when he had lost his way.

The work was a dismal failure in Paris at its premiere in 1846, but was much better received abroad. After his first concert in Drury Lane, London in 1848, he wrote: `my music has caught these English audiences like fire on a trail of gunpowder. I had the very devil of a reception, I had to repeat two of the scenes from Faust and all the press notices were favourable’. Indeed, Faust was one of Berlioz’s favourites among his own works, but he couldn’t get it performed for economic reasons; a good performance needs a huge amount of chorus rehearsal, not to mention top-flight soloists and orchestra.

This Faust has a feel-good association for Elder, as he remembers how striking that 1969 ENO production (by Michael Geliot, conducted by Charles Mackerras) was. He remembers how avant-garde it seemed, with the use of film conjuring up extraordinary dream-like images. `It was strongly cast (with Raimund Herincx, Alberto Remedios and Janet Baker) and I saw it from very high up, a long way away, and there were two red setters in it.’ Although Elder has conducted the work in Australia and at the Proms, this will be the first time he has performed it in the theatre.

Elder is sure Berlioz did envisage Faust on the stage. `He certainly dreamt about it – he wanted to write an opera on the Romeo and Juliet story and told a friend that he was writing a four-act Faust opera. Though he was an innately theatrical composer, he knew his dream could never come true. So he had to be practical. After the disastrous premiere of Benvenuto Cellini, he reckoned that his chances of getting his music heard would be better if he tried to write within the confines of the concert hall. But I’m sure he didn’t compromise himself in what he wrote. He thought of the concert hall, but his responses to the words and the situations were theatrically motivated. This is why one can take the orchestra into the pit, because you immediately have the feeling that the music belongs there. And luckily for us, he eventually came back to the theatre with The Trojans and Beatrice and Benedict.

So the fact that The Damnation is not really an opera doesn’t matter a damn, especially in these days of such disparately conceived theatrical repertoire. `As with any operatic production whether it’s convincing in the theatre depends on the tone of the performance and whether the design, the production and the music-making come together in a well-balanced whole. You can describe it as a dream, because it moves so sharply, it changes mood as fast as the imagination can change, as quick as light, much faster than complicated theatrical scenery can change, so the lighting is literally very important if you do this work in the theatre. We’re going to present the four parts without an interval which gives a terrific momentum to what is a very short evening. Everyone has to be like chameleons, they’ll have to change the colour of what they do just like that!

Elder agrees that the orchestra will be in for a good time, rehearsing and performing this score. `More than any other composer of his generation, Berlioz treated the orchestra as a cauldron of colour. He stretched the ways in which orchestral sound could be broken down and made up again, and pushed the instruments beyond the frontiers of what was routine and comfortable. Indeed, he was capable of inventing new sounds, and of experimenting until he was sure he got what he dreamt of.

`Though it’s often the case in opera that crucial events of the story happen off-stage, this piece is the most extreme. It’s a series of pictures of aspiration and hope and failure and disillusionment. After all, the bare bones of the story are simple. Faust is an immensely learned, high-achieving man, but he feels unfulfilled and aspires to the happiness that eludes him. When Mephistopheles [the devil] suddenly appears and offers him the world, it’s an offer he can’t refuse. Mephistopheles then whisks him off to different localities, different atmospheres, to give him a chance before it’s too late to find the woman of his dreams, he offers him sensuality. But it’s all a chimera. You could say that it’s a piece about people being alone. These characters never really contact each other, nothing is ever fulfilled and a deep, Romantic yearning finally hits Faust when he pits himself against the whole of nature, before finally tumbling down as Mephistopheles’ slave.

`I think it’s a great operatic event, and it’s good to label it in that way. There are three wonderful singing-acting roles of great colour, magnitude and challenge, and the chorus has to be immensely flexible – happy and light, fleet of foot one moment, worshipping the next, drunk the next. It gives them a marvellous evening, with very thrilling music to sing, ending up in hell of course, with the men singing the nonsense language of the damned.

`Berlioz is a one-off, his phrase lengths are very elusive, in a way that Gounod’s or Mendelssohn’s phrase lengths are not. When you start at the beginning you must feel the whole span of the work right to the end. He was an eccentric, a visionary, like a French Tippett in a way. He wrote what came from his amazingly vivid, individual and uncompromising musical imagination without caring whether or not it fitted into prescribed conservatoire trained moulds. As a personality he was totally original. You have to be inside that eccentricity, you have to love it. That’s not a problem for me – I certainly do.’