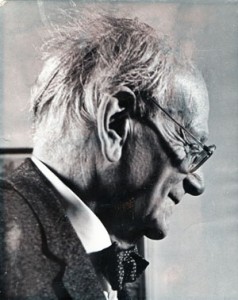

Viennese School – Amanda Holden remembers Egon Wellesz

Opera, Festivals 2003, pp.50-3

Wellesz’s long life was divided in two by the Second World War. After the First World War and his childhood and education in Vienna, he lived and worked there as a composer, primarily of stage works, and a musicologist; but during the Second World War he moved to Oxford, where he turned to symphonic composition and became an influential and much-loved teacher at the university. When I arrived to study music in 1966 and heard that, since there were no music dons at women’s colleges, Dr Wellesz was to be my tutor, I had never heard of him; he was then 81 years old (and I was 18).

His passionate interest in opera had begun before the turn of the century. Aged 14 he heard Mahler conduct Der Freischutz at the Hofoper and immediately resolved to devote his life to music, as he told me: ‘the next morning I started composing and since then I have never stopped’. While at the Institute of Musicology, studying under Guido Adler, the great musicologist and a close friend of Mahler, he also enrolled ‘with a few friends’ (by whom he meant Berg and Webern), in Schoenberg’s private composition class. He described Schoenberg as ‘an unknown young composer who rebelled against the conservatory traditions.’ As a teacher he was: ‘Forbidding! He used to walk up and down, always smoking. He was immensely severe, but also inspiring…’. Together, Webern and Wellesz studied the Viennese classics, Brahms and Strauss, and they used to play Mahler symphonies arranged for four-hands (‘we were both frightfully bad pianists’), before going along to all Mahler’s rehearsals and performances; Wellesz always illustrated my tutorials with examples from early editions and his own vivid first-hand memories.

Whilst becoming a composer, Wellesz was also forging a distinguished academic career. As it was impossible to make a living from composition this seemed to him a more attractive alternative to being a conductor (‘doing unimportant work performing operettas on small stages’), and he was anyway voraciously curious about the history of music. He wrote his doctoral thesis (1908) on the works of Giuseppe Bonno (who, not unlike Wellesz, worked in Vienna with the leading names of his time – in Bonno’s case Gluck, Metastasio, Mozart, Salieri) and went on to make detailed studies of early opera, publishing work on Fux and Venetian opera, particularly Cavalli. Following a suggestion from Hanslick he also began investigating oriental influences on Austrian music, which inspired him to study of eastern church music and painstakingly to decipher Middle Byzantine notation, considered by some to be his most distinguished achievement.

So, despite his strong roots in the Viennese tradition and his membership of an extraordinary artistic melting pot, which included e.g. Rilke and Kokoshka (who painted Wellesz’s portrait in 1911). Wellesz had a boldly international outlook both in his research and activities as a composer. On his first trip to England in 1906 he met Edward J. Dent in Cambridge and together they later founded the ISCM (International Society for Contemporary Music) at a festival of modern chamber music in Salzburg in 1922 – it was thanks to Wellesz that Bliss, Vaughan Williams, Holst and Walton were first heard abroad. Other travels included a congress on Arab music in Cairo for and research trips to the near east with both Bartók and Hindemith. In 1932 Wellesz received an honorary doctorate at Oxford, the first Austrian composer to be so honoured since Haydn, and Wellesz also participated actively with Schoenberg in the avant-garde Verein für Musikalishe Privatauffuhrungen (Society for Private Musical Performances) and became his first biographer, publishing an astute study of Schoenberg’s life and works(so far) in 1921.

At the start of the First World War, Wellesz embarked on his first stage work (though it was not premiered until 1924). Inspired by performances in Vienna by the Ballets Russe of Stravinsky and Rimsky-Korsakov as well as his own exhaustive studies of baroque opera, Wellesz quietly forged his own brand of Gesamtkunstwerk, quite independent of Wagnerian influence. In the nine operas and ballets he completed by the end of the 1920s, he gave as much prominence to dancing and choral singing as to the soloists; and when I studied with him he was still obsessed with Greek drama as the true precursor of opera; it isn’t at all surprising that the majority of these works are based on ancient stories.

First came a ballet Das Wunder der Diana, to a scenario by Bela Balász (writer of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and The Wooden Prince) whom Wellesz met with Bartók on a visit to a festival in Budapest in 1911 (Bartók was so impressed by the young composer that he immediately arranged the publication of Wellesz’s early works). Next came the first opera Die Prinzessin Girnara which arose from an encounter in 1918 with the playwright Jakob Wassermann, who wrote the libretto based on his own novel. At the same time Wellesz met Hugo von Hofmannsthal; they became close friends and in the midst of his work with Richard Strauss Hofmansthal wrote both the scenario for Wellesz’s ballet Achilles auf Skyros and the libretto for his opera Alkestis. These two works along with a third opera Die Opferung des Gefangenen formed what Wellesz called his Heroic Trilogy.

Another opera followed, a short chamber comedy based on Goethe’s Scherz, List und Rache, before Wellesz embarked on his penultimate opera Die Bakhantinnen. The idea came from Hofmannsthal who had planned to write a drama based on the tragedy of Pentheus. Wellesz immediately immersed himself in Euripides’s play and wrote the libretto himself, taking it to Hofmannstahl in 1929 (shortly before the latter’s death). Further encouraged by Hofmannsthal’s enthusiasm, Wellesz set to work and completed the opera by the end of 1930. It opened at the Staatsoper in Vienna on 20 June 1931 directed by Lothar Wallerstein. It was designed by Alfred Roller, the founder (along with Kokoshka, Schiele and Klimt) of the Secessionists, who had designed the premieres of Der Rosenkavelier and Die Frau ohne Schatten; the conductor was the great Straussian Clemens Krauss, who insisted on 60 chorus and 20 orchestral rehearsals for the piece. The music is hard to classify, not surprisingly for a composer from such a widely and wildly eclectic background; jagged atonal lines are contrasted with unashamedly lyrical melodic passages almost in the English pastoral tradition; rhythmic dance music redolent with flavours of Strauss and Stravinsky is juxtaposed with vast homophonic choral music influenced by their composer’s studies of eastern choral traditions. But the work holds together seamlessly, assisted by Wellesz’s admirably clear libretto.

In March 1938, Wellesz was in Amsterdam with Bruno Walter, who was to conduct a performance of Wellesz’s three-movement symphonic poem for large orchestra Prosperos Beschwörungen (Prospero’s Entreaties) which Walter had successfully premiered at the Musikverein in Vienna, when the news came of Hitler’s invasion of Austria. Wellesz was partly Jewish (though like Mahler he had converted to Catholicism) and was strongly advised not to return home. Thanks to the links he had forged, he was able to escape to England, though at first he was interned on the Isle of Man. It was a grim time, possibly the worst of his life, not knowing if he would see his wife (in 1908 he married the art historian Emmy Stross) and daughters again. But Dr Henry Colles (then chief music critic of The Times and editor of Grove) helped Wellesz to secure a Fellowship of Lincoln College, Oxford in 1943. The family was reunited and they set up their home at 51 Woodstock Road, Oxford. From there, for almost thirty years, Wellesz would set off on foot to teach at the Music Faculty, always immaculately dressed in a three-piece tweed suit and bow tie, doffing his hat and greeting his many friends with charming politesse in a strong Viennese accent.

Wellesz had written no music during his five years of trauma, but with his arrival in Oxford a new lease of life came over him, embodied in the 5th String Quartet and a lyrical setting of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo (a work he was always particularly fond of). Then, quite suddenly, in 1945 at the age of 60, he found himself (as he put it), completing a symphony in only three weeks, the score is dated 1 January 1946; it was premiered that year by the Berlin Philharmonic under Sergiu Celibidache. He continued to compose for the next 25 years; symphonies, vocal, choral, solo and chamber music poured forth, including, in 1951, his last opera, Incognita, for the University Opera Club, to an English libretto based on Congreve’s first novel.

In today’s climate it’s perhaps worth reflecting upon some comments made by Wellesz in a series of three lectures on opera that he delivered to London Music college students in 1950: `Opera cannot play the role of a casual visitor in the life of a nation. Wherever opera has flourished, it has been accepted as an important factor in the nation’s spiritual life. Every effort has been made to give it a permanent place among the activities of the human spirit, which are the justification of our civilization. The action on the stage in an opera must be intelligible to the public, or the music will fail to hold their interest. Opera in England therefore, must be sung in English. Only then will it be possible for the whole audience to be united… and to experience, as in the theatre, the emotions of the drama.’

In 1970 I took part in two concerts to celebrate Wellesz’s 85th birthday; at the Austrian Institute in London and in the Holywell Music Room in Oxford, and at the start of the vacation the following summer, I remember asking Wellesz how he planned to spend his holiday. He said he had a dilemma, ‘either I write a symphony, or I write my memoirs’. The ‘dilemma’ was perhaps more profound than I realised; the ninth symphony he had decided to write was to be his last work; the memoirs never did get written, but I think he knew it had to be thus. Following the completion of the symphony he suffered a stroke and died in Oxford; he now rests in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna alongside his musical ancestors, teachers, colleagues and friends, richly deserving of his place among them.